BLOG

Affordable upstate

Workforce Housing vs. Class A Apartments: Why “Affordable” Matters for Investors

What Are Class A vs. Class B/C Apartments?

In multifamily real estate, properties are commonly classified by quality and price point. Class A apartments are the luxury units – typically newer buildings with high-end amenities, prime locations, and top-tier rents. These might be downtown high-rises or upscale suburban complexes built in the last 10-15 years. By contrast, Class B and Class C apartments (often called “workforce housing” or the “missing middle” of the housing market) are more modest, naturally affordable units. They are usually older properties (think 1980s-2000s builds for Class B, even older for Class C), with fewer frills and more basic finishes. Rent prices for Class B/C apartments are lower, targeting middle-income households rather than high earners. In essence, workforce housing represents that middle segment between subsidized low-income housing and luxury developments – providing decent, accessible homes for the average worker.

Tenant demographics differ between these classes. Class A tenants often include young professionals, executives, or affluent downsizers who can afford premium rents for upscale amenities and locations. Class B/C tenants are typically middle-income workers – teachers, nurses, police officers, retail managers, manufacturing technicians – essential community members who earn roughly 60% to 80% of area median income. These residents seek safe, clean housing within their budget, often near employment centers. They may not need a rooftop pool or concierge service, but they value affordability and reasonable quality. Understanding these distinctions is key for investors, as it sets the stage for differences in demand, rent growth, and investment performance between luxury and workforce multifamily properties.

Rent Levels and the Affordability Gap

One striking difference is the rent price gap between luxury Class A units and naturally affordable Class B/C units. Nationally, Class A apartments command significantly higher rents – often hundreds of dollars more per month. In mid-2023, Cushman & Wakefield reported the average rent premium for Class A over workforce housing to be about $650 more per month(multifamily.cushwake.com). Even when luxury landlords offer concessions or discounts, the price difference remains substantial. This means a family renting a Class B apartment might pay, say, $1,200 per month, whereas a comparable Class A unit in the same city could be $1,850+. For many middle-income renters, “trading up” to luxury is financially out of reach. As a result, they tend to stay in Class B/C housing, keeping demand high.

In markets like Greenville–Spartanburg, SC, this affordability gap is evident. The influx of new upscale developments has pushed average asking rents in the Upstate South Carolina region to around $1,333 per unit as of late 2024 (whosonthemove.com). Those new deliveries are mainly Class A projects with high-end finishes. Meanwhile, older and modest properties remain much more affordable – often several hundred dollars below that average. The “missing middle housing” (duplexes, fourplexes, garden apartments, etc.) has seen little new construction in recent years, so existing Class B/C units face diminishing supply. In fact, CBRE research notes that over 100,000 older affordable units are removed from the U.S. market each year (due to obsolescence or redevelopment)stessa.com. This shrinking supply of workforce housing, combined with the rent gap, creates a classic supply-demand imbalance: plenty of renters need mid-priced homes, but new supply is mostly luxury. For investors, this means workforce housing properties often enjoy less pricing pressure and more consistent tenant demand than their pricier Class A counterparts.

Occupancy Trends: Stability in Workforce Housing

One of the biggest advantages of Class B/C multifamily is its track record of high occupancy and stable demand. Because they serve an “essential” slice of the renter pool, workforce housing properties typically see lower vacancy rates than luxury complexes. For example, prior to the pandemic, vacancy rates in Class B and C apartments were at all-time lows (around 5%) and remained in the low single digits (stessa.com). Even during economic swings, many renters simply cannot afford to leave workforce housing – there aren’t cheaper alternatives that offer the same quality of life. This keeps occupancy elevated. By contrast, Class A buildings experience more churn; renters have more options (including homeownership or moving to cheaper units if budgets tighten).

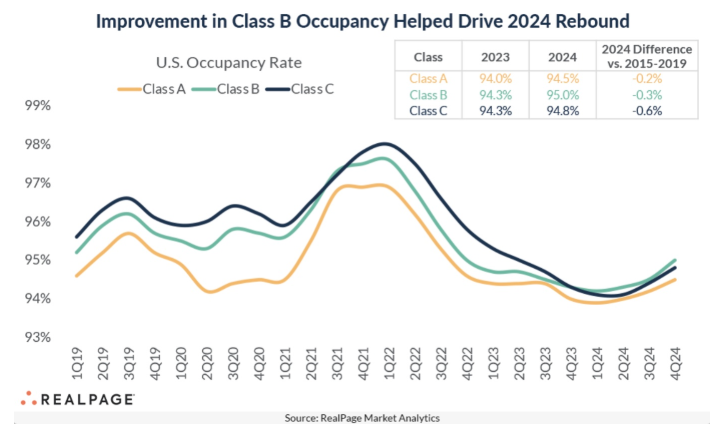

Recent data underscores this resilience. In

2024, despite a flood of new apartments hitting the market,

Class B units led the nation in occupancy gains. By the end of 2024,

Class B apartments reached about 95% occupied, slightly

outpacing Class A (94.5%) and Class C (94.8%) nationally (yieldpro.com). This was a notable shift – historically Class C (the cheapest segment) often had the highest occupancy, but the strong absorption of mid-tier units has pushed Class B to the top. In effect,

workforce housing is staying full even while luxury lease-ups compete to find tenants. Industry analysts attribute this to the broad renter base for affordable units and the fact that

new supply is overwhelmingly targeting the high end, leaving

mid-priced rentals undersupplied. Even with a 50-year high in overall apartment construction deliveries in 2024, the

rebound in demand has been strongest in Class B properties.

In Upstate South Carolina, a similar pattern appears, albeit with local nuances. The Greenville-Spartanburg market has been booming with new development (over 1,300 new units delivered in late 2024 alone), which caused a temporary uptick in vacancy as those units lease up (whosonthemove.com). Overall market occupancy in the region hovered in the high-80s to around 90% during that supply wave. However, it’s important to note that much of the new supply is Class A luxury, which typically opens with some empty units as they attract renters. The underlying demand for workforce housing remained robust – Class B/C communities in the area generally stayed near full, as local workers and new migrants sought affordable places to live. In fact, Colliers reports that after years of rapid building, strong absorption by late 2024 actually boosted the Upstate’s overall occupancy above 89% for the first time since 2022, suggesting the market is quickly soaking up new units thanks to population growth. For passive investors, the takeaway is that well-located Class B apartments tend to have steady, reliable occupancy. Fewer empty units means more consistent cash flow and less revenue lost to vacancies.

Rent Growth and Returns: “Affordable” Doesn’t Mean Less Profitable

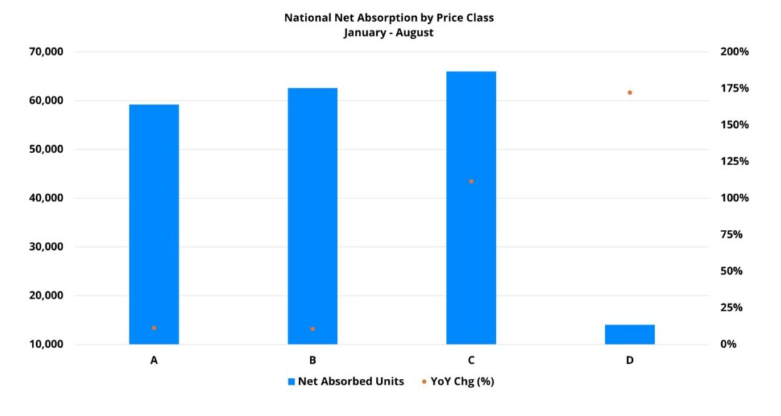

There’s a misconception that because workforce housing charges lower rents, it must yield lower returns. In reality, “affordable” does not mean unprofitable. Investors often find that Class B/C properties can deliver very competitive returns, thanks to solid rent growth and higher initial cap rates (pricing). Rent trends in recent years illustrate how mid-tier apartments can hold their own. Coming out of the pandemic, luxury Class A rentals did see a spurt of high rent growth in 2021–2022 (as affluent renters rushed back to cities and new upscale supply was absorbed). By early 2023, Class A annual rent growth nationally was about 5.7% year-over-year, slightly ahead of Class B’s ~4.6% growth (realpage.com). However, that gap didn’t last. As economic conditions normalized and a wave of new Class A supply hit the market, luxury rent growth cooled. Meanwhile, Class B rent growth stayed more steady. By mid/late 2024, data showed Class B outpacing Class A in rent gains – for example, through August 2024, Class B effective rents were up ~2.5% year-to-date, versus ~2.0% for Class A (alndata.com). In other words, the once red-hot luxury segment slowed to a modest growth rate, while the workforce segment kept chugging at a similar or better pace.

Why is this important for investors?

Steady rent growth coupled with high occupancy means reliable income streams. Class A assets might boast higher absolute rents, but they also can experience rent

volatility – soaring in boom times but flattening or even declining when supply outstrips demand. We see this in many Sun Belt markets where thousands of new upscale units forced Class A landlords to offer free rent and concessions in 2023–2024 (mrisoftware.com). Class B owners, by contrast, seldom need to give large concessions; their rents are already at a value point that draws consistent demand. Additionally,

initial cap rates (investment yields) on Class B/C properties are often higher than on trophy Class A buildings. An investor might acquire a workforce housing complex at a, say, 5.5% capitalization rate, whereas a luxury asset in the same city might trade at 4.5%. The higher yield, combined with stable rent growth, can produce strong cash-on-cash returns. And if the investor adds

value (through renovations or better management), workforce housing offers upside potential as well – upgrading an outdated Class B property can push rents up while still keeping units affordable to a broad renter base. Many Class B/C deals are

value-add opportunities that benefit from improving the property (new appliances, updated flooring, etc.) and capturing higher rents, all while demand remains deep.

Moreover, exit strategies for workforce housing can be favorable. Because these assets provide solid yield and social impact, there’s robust demand from other investors and even institutional funds for stabilized affordable multifamily. Recent years have seen growing recognition that the “missing middle” segment is under-served and poised for long-term demand, which can support favorable valuations. All told, a well-bought Class B/C asset can appreciate in value through income growth and cap rate compression, delivering a compelling total return that rivals or exceeds more glamorous properties. The key is that returns in workforce housing are driven by occupancy and long-term demand, not just luxury rent premiums.

Recession Resilience and Risk Factors

Perhaps the most compelling reason passive investors gravitate toward workforce housing is its recession resilience. While no real estate investment is completely “recession-proof,” history shows that mid-priced apartments weather economic storms better than luxury complexes. During the 2008 Great Financial Crisis (GFC), for instance, many high-end apartment projects struggled with vacancies and rent concessions as job losses hit young professionals and would-be homebuyers. Workforce housing, however, outperformed during the GFC, maintaining more stable occupancy and collections (multifamily.cushwake.com). The logic is simple: even in a downturn, people need affordable places to live. If anything, demand for affordable rentals can increase in tough times – renters downgrade from Class A to Class B, or delay plans to buy a house and stay in an apartment. Higher-income tenants have options (and may leave expensive rentals), but middle-income renters are more likely to keep renting what they can afford, prioritizing housing payments in their budgets. This dynamic insulates Class B/C to a degree. A pre-pandemic Fannie Mae analysis projected that in a hypothetical recession scenario, Class A vacancies could exceed 10% while Class B/C vacancies would remain in the mid-5% range (stessa.com). In other words, luxury apartments might see double the vacancy rate of workforce housing during a downturn, due to their greater economic sensitivity.

We saw a real-world test of resilience during the 2020 COVID-19 downturn as well. Initially, there were concerns about rent payments across all classes. But over time, Class B/C properties held up relatively well in occupancy. In fact, after the initial shock, many Class A urban buildings faced more vacancy (as remote workers left expensive cities or sought more space), whereas suburban Class B apartments filled up with renters seeking cheaper housing. Fast forward to the recent cycle: in early 2024 the apartment market experienced a soft patch (occupancy nationally dipped to ~94.1% in Q1 2024 amid record new supply) (yieldpro.com). Yet even then, workforce housing demand remained steady, and by Q4 2024 overall occupancy rebounded to ~94.8% – near long-term norms – largely thanks to strong absorption in Class B units (yieldpro.com). Class B was the first segment to fully bounce back, rising by 0.8 percentage points in occupancy by late 2024, more than the gains in Class A or C. This illustrates a key point for risk: Class A has a higher “beta” – it’s more volatile with the market cycle – while Class B/C has a stabilizing effect in a portfolio.

That said, investors should also understand the risks unique to each class. Class A investments carry the risk of oversupply (developers love building luxury units when capital is cheap, which can lead to competitive leasing and rent softness). They are also more economically sensitive – a tech company layoff or a slowdown in professional hiring can quickly hit luxury rentals in a city. Class B/C investments, on the other hand, face risks around tenant financial stability and property age. Workforce renters may have less savings and could be more vulnerable if they lose jobs (so diligent tenant screening and diversified employment bases are important). The properties themselves are older, which means higher maintenance and capital expenditure needs – roofs, HVAC, and appliances may need replacement, and dated interiors might require upgrades to remain competitive. However, these risks can be mitigated with proper asset management and by investing in strong locations.

Notably, in a place like Greenville-Spartanburg, many Class B/C communities benefit from being in proximity to stable employment hubs (manufacturing plants, logistics centers, hospitals, universities). For example, the Greer submarket (between Greenville and Spartanburg) has seen explosive job growth in manufacturing (BMW, Michelin, etc.) and revitalization of its downtown – attracting an influx of middle-income workers. Those workers need housing they can afford, and they provide a reliable tenant base for well-kept Class B apartments. As long as an investor conducts thorough due diligence – ensuring the property is in a strong job market with diversified employment – the risk of prolonged vacancies in workforce housing remains relatively low.

Upstate South Carolina Case Study: Resilient Demand in a Growing Market

The Greenville–Spartanburg, SC region (often called “Upstate SC”) offers a timely example of how workforce housing can shine, especially in high-growth markets. Over the past few years, Upstate SC has been one of the fastest-growing areas in the country. From 2023 to 2024 alone, South Carolina’s population grew by 1.7%, adding 91,000 new residents (dew.sc.gov). Spartanburg’s metro area was the 10th-fastest growing in the U.S., expanding by about 2.7% in one year. Much of this growth is driven by domestic migration – people moving in from other states for jobs, affordability, and quality of life. Greenville and Spartanburg counties consistently rank among the top destinations for inbound moves.

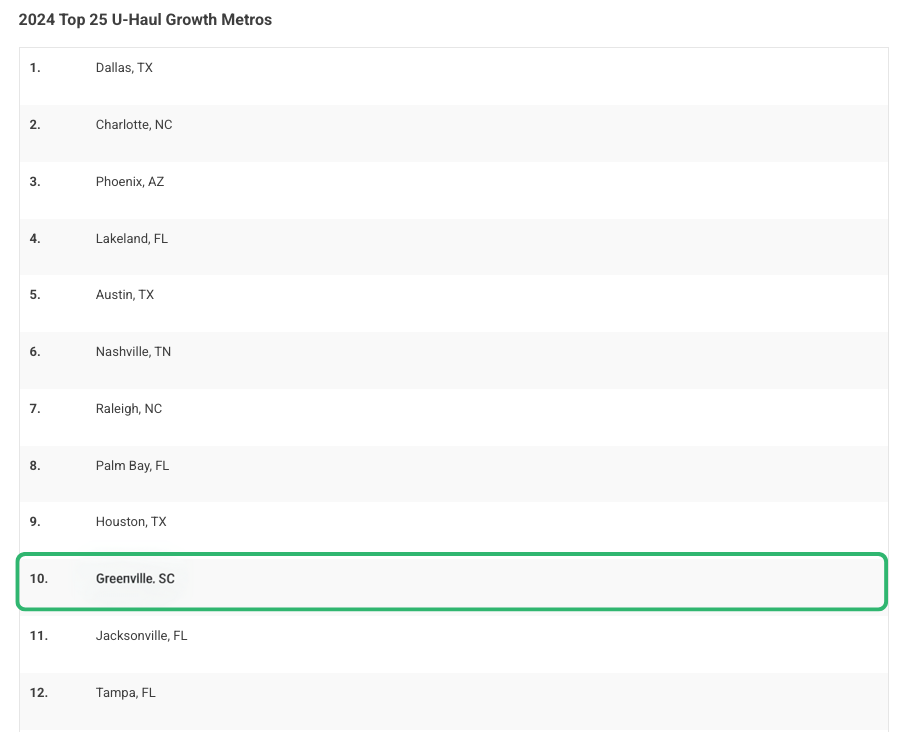

That trend has only accelerated in recent years. According to U-Haul’s 2024 Top 25 Growth Metros report, Greenville ranked among the top 10 most moved-to metro areas in the U.S., reflecting its growing national appeal as a relocation destination (uhaul.com). Additionally, South Carolina ranked as the #1 growth state based on one-way U-Haul rentals, surpassing traditional leaders like Texas and Florida. This data reflects a clear and ongoing migration boom—especially from high-cost states—bringing thousands of new residents to the region who need access to quality, affordable housing.

This surge of population has translated into strong housing demand at all levels. Developers responded by building thousands of new units – however, the vast majority of new apartment construction in Upstate SC has been Class A luxury communities. As mentioned, roughly 20,000 new units were delivered in the past five years (whosonthemove.com), pushing the market’s total inventory to new heights. These shiny new complexes typically target top-of-market rents (often catering to newcomers used to big-city rents, or local high earners). While absorption of new units has been good, the heavy supply caused the overall vacancy rate to tick up temporarily in 2023-2024. Yet, tellingly, workforce housing properties in the region remained near full. Local operators of Class B apartments frequently report waitlists or quick lease-ups for any vacant units, because demand from local workers far exceeds supply in the mid-priced rental category. The Greenville area’s average rent of ~$1,300 covers a wide spectrum – new downtown flats might be $1,800+, whereas an older suburban 2-bedroom might rent for $1,000 – and it’s that latter segment that sees endless renter demand.

Upstate South Carolina’s economy provides a sturdy foundation for workforce housing. The region’s job growth is diversified across manufacturing, logistics, healthcare, and professional services. Companies like BMW, Volvo, Michelin, and Boeing (nearby in North Charleston) have created a manufacturing boom, while Greenville’s emergence as a tech and education hub draws young talent. These industries employ thousands of “missing middle” income earners – folks who earn too much to qualify for subsidized housing but not enough to comfortably afford a luxury apartment or single-family home. For instance, a BMW assembly technician or a hospital nurse might earn $50k-$70k per year; they prefer rental options in the $900-$1,300 per month range, which is the sweet spot for Class B/C units. As a result, occupancy in well-managed workforce housing around Greenville and Spartanburg tends to stay high even if new luxury flats down the road are offering a free month’s rent to fill units. The region’s multifamily reports note that multifamily demand is bolstered by the area adding over 30,000 residents per year via in-migration (whosonthemove.com) – a trend that is forecast to continue. This influx supports steady rent growth. Indeed, despite a lot of construction, the Upstate saw rent growth remain steady (though moderate) even as supply peaked, a sign of the persistent demand.

For passive investors considering markets like Greenville-Spartanburg, the implication is clear: investing in workforce housing aligns with powerful demographic and economic tailwinds. You are effectively supplying a product that the market sorely needs – clean, affordable homes for the very workers fueling the region’s growth. Not only can this strategy yield stable financial returns, but it also carries a feel-good component of community impact (housing teachers, nurses, and factory workers who make the local economy run). It’s truly a case where you can do well and do good.

Impact and “Missing Middle” Opportunity

Beyond the numbers, many passive investors are drawn to Class B/C multifamily for the tangible impact it has. Investing in workforce housing often means revitalizing older apartment communities, improving living conditions for residents, and preserving affordability in a market that might otherwise price out essential workers. It’s sometimes called “missing middle housing” investment because it fills the gap between low-income housing (often government-subsidized) and luxury developments. By putting capital into these properties, investors help ensure that cities maintain a stock of reasonably priced housing for middle-class families. This has socio-economic benefits: it stabilizes communities, reduces commuter burdens (people can live near where they work), and supports local businesses with a steady customer base of nearby residents.

From an investment perspective, focusing on the missing middle can also be seen as forward-thinking and defensive. With housing affordability a growing challenge nationwide, there is increasing political and social attention on preserving and creating workforce housing. Some cities and states are even offering incentives for developing or maintaining affordable units. While our focus here is on naturally occurring Class B/C stock (not deed-restricted affordable housing), the broader trend is favorable – affordable rentals will remain in high demand, and policies may further encourage investment in this segment. By contrast, luxury housing can sometimes face community pushback (the proverbial “luxury condos while locals can’t find housing” narrative) and is more dependent on a smaller pool of well-heeled renters.

It’s also worth noting that workforce housing demand is less “fad-driven.” Luxury properties might try to one-up each other with fancy amenities (from golf simulators to dog spas), essentially engaging in an arms race to justify premium rents. While that can attract a segment of renters, it also adds to operating costs and can become outdated as trends change. Workforce housing, on the other hand, competes on fundamentals: price, location, and basic quality of life. Investors can add value by ensuring properties are safe, clean, and well-managed – things that never go out of style for renters. Simple upgrades like energy-efficient appliances, on-site security, or playgrounds for kids can enhance appeal without breaking the bank. And because the tenant base is broad, marketing a Class B community is about reaching the general workforce population, which is always renewing itself (new graduates, people moving for jobs, etc.). This contributes to lower leasing risk and turnover costs relative to a niche luxury building that might cater to a narrow demographic.

Conclusion: Steady Returns and Community Wins

For passive real estate investors seeking stable, recession-resilient opportunities, workforce housing (Class B/C multifamily) presents a compelling case. The key differences between Class A luxury and Class B/C housing – in tenant profile, price point, and performance – all point toward the latter being a dependable workhorse in an investment portfolio. Class A apartments can certainly thrive in boom times, but they also ride more ups and downs. Class B/C properties offer steadier occupancy, reliable rent collections, and a deep pool of demand that persists through economic cycles. As one industry blog succinctly put it, while no asset is entirely recession-proof, workforce housing tends to be less susceptible to downturns because demand for an affordable place to live “remains constant” (colonyhillscapital.com). Landlords of these properties often enjoy lower vacancy and consistent cash flow, even when luxury projects in the same city are struggling to fill units.

In today’s market (2023–2025), data shows that workforce housing is holding strong. Occupancies for Class B/C are in the mid-90% range in many areas, often outperforming Class A on this metric (yieldpro.com). Rent growth, while modest compared to the frenetic pace of 2021, has been positive and stable for affordable units – and even outpacing Class A in some cases (alndata.com). Meanwhile, macro trends like net migration to affordable regions (the Southeast, Midwest, etc.) and a shortage of middle-income housing supply act as tailwinds for the sector. In places like Upstate South Carolina, the story is especially upbeat: rapid population and job growth, coupled with a high cost-of-living influx from relocators, is keeping demand high for every decent, affordably priced apartment.

Crucially, “affordable” does not mean sacrificing returns. Investors in Class B multifamily can achieve healthy yields and long-term appreciation, all while mitigating downside risk. The combination of reasonable purchase prices (often below replacement cost per unit), value-add potential, and enduring renter demand often leads to a favorable risk-adjusted return profile. And beyond the numbers, there’s a pride of ownership in providing quality housing to the backbone of the community – the nurses, teachers, technicians, and service workers who make the city hum. This community impact angle resonates with many passive investors who want their capital to do more than just generate profit.

In summary, when comparing workforce housing vs. luxury apartments, the differences are clear: Class A offers glitz and higher highs, but Class B/C offers grit and consistent performance. For passive investors educated on these distinctions, investing in workforce housing can be a savvy strategy – leveraging recession resilience, stable occupancy, and solid returns, all while addressing a critical housing need. In a world of flashy developments, the unassuming Class B apartment community might just be the quiet hero of your portfolio, delivering steady cash flow through good times and bad. Affordable does not mean less profitable; in fact, it can mean durability and dependability – qualities any investor should value in the long run.

Sources

Sources:

- SC Dept. of Employment & Workforce – 2024 Population Estimates: Migration Drives Rapid Growth in South

- U-Haul Growth Index 2025 – U-Haul Growth Metros and Cities of 2024: Dallas Top Metro for In-Migration

- Colliers South Carolina – Q4 2024 Greenville-Spartanburg Multifamily Report

- Cushman & Wakefield – U.S. Multifamily MarketBeat Q2 2023

- YieldPro Magazine – "Class B Apartments Lead Occupancy Increases" (Jan. 30, 2025)

- ALN Apartment Data – "Uneven Performance Between Price Classes" (Aug. 2024)

- Colony Hills Capital Blog – "Why Invest in Workforce Housing" (Feb. 15, 2024)

- Veritas Equity Partners – "Workforce Housing: A Smart Investment"

- Stessa (with Fannie Mae insights) –

"What is Missing Middle Housing?" and market performance trends (2019–2020)